Face Recognition Research in October

In this post I will briefly review some of the face recognition papers that were submitted to arXiv in October.

Quantifying the Extent to Which Race and Gender Features Determine Identity in Commercial Face Recognition Algorithms

by John J. Howard, Yevgeniy B. Sirotin, Jerry L. Tipton and Arun R. Vemury.

In this paper the authors study, how much commercial face recognition algorithms (CFRAs) rely on gender and race features to determine identity. Previous work has shown that face embeddings contain a lot of information about gender, race and even attributes unrelated to identity such as the presence of glasses. Other work hypothesised that removing gender information from face embeddings using, for example, adversarial training will lead to less biased models, but achieved only mixed results. The current paper looks at the same problem in the context of commercial algorithms. The main difference is that commercial algorithms do not expose the face embeddings, but only a similarity score thus reducing the information available to researchers.

The authors use images from 333 test subjects from four groups (white/black, male/female) to evaluate five CFRAs, which remain anonymous. As a baseline, they compare the results with a commercial iris recognition algorithm (CIRA), because the accuracy of iris recognition is not correlated with demographic attributes.

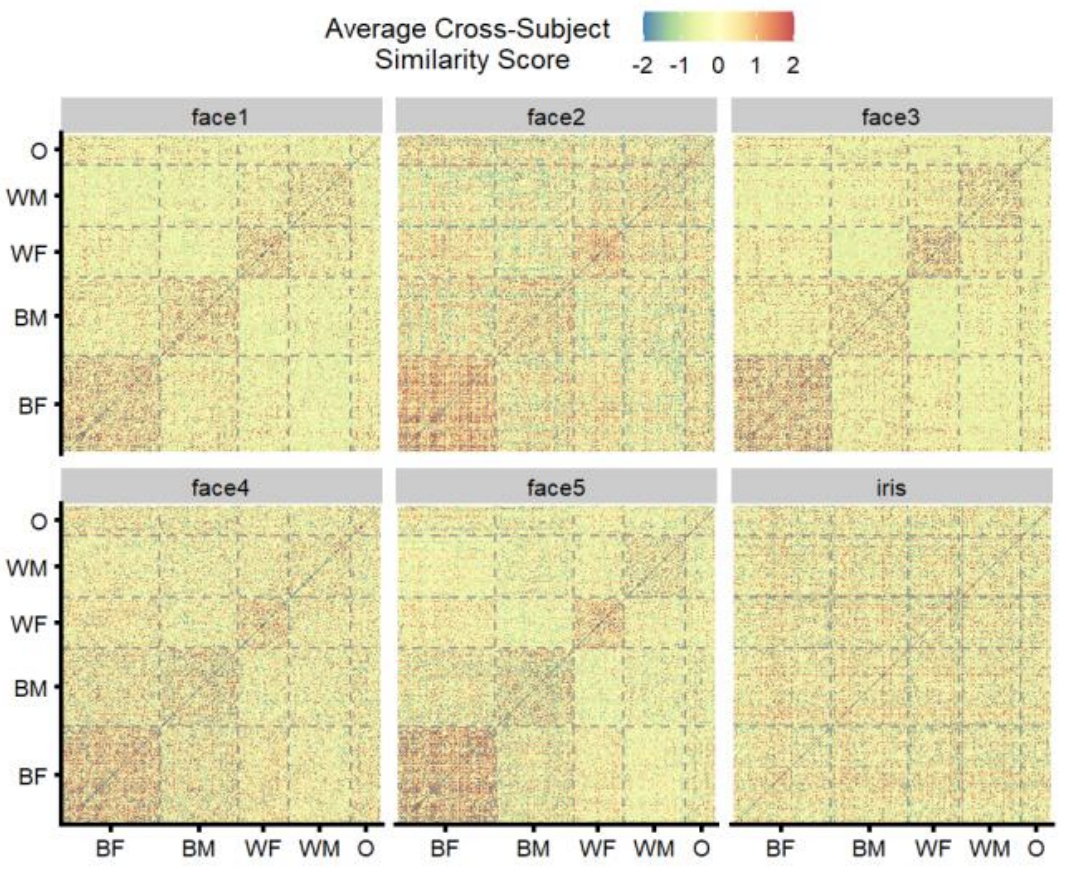

The authors observe that CFRAs produce higher similarity scores within demographic groups than across demographic groups, leading to a block-diagonal structure for the score matrix. This block-diagonal structure is reminiscent of a similar structure for FMR heatmaps, e.g. in the NIST’s FRVT reportcards. In the figure below scores have been normalised such that non-mated scores have \(\mu=0\) and \(\sigma=1\).

Fig. 3 in the paper.

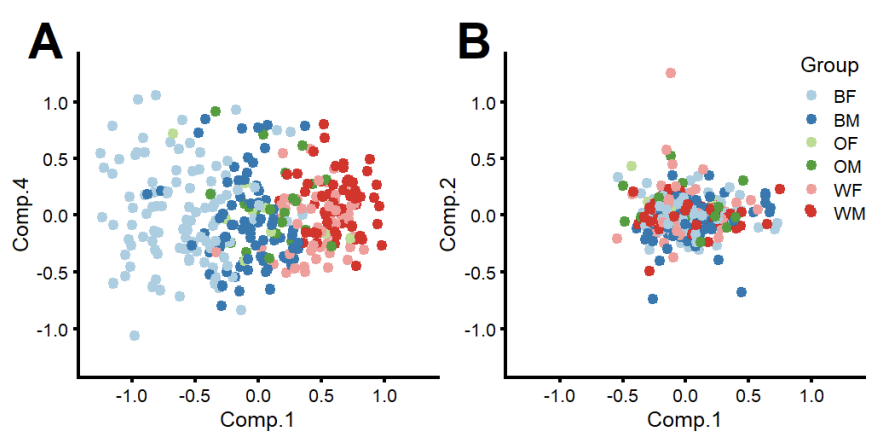

The authors then perform PCA on each similarity matrix. The principal components then correspond to score patterns and we can ask, to what extent principal components are aligned to demographic attributes. The figure below shows clear alignment between the first component and demographic groups for the face recognition algorithm, while no such alignment can be seen for iris recognition.

Fig. 4 in the paper. A. Components 1 and 4 for face. B. Components 1 and 2 for iris.

The visual evidence looks compelling and the authors proceed to quantify the proportion of score variance in each principal component that is explained by gender and race information. To do that they define the clustering index \(C_k\) for principal component \(k\),

\[C_k = \frac{\sum_D \sum_{j \in D} (x_j - \overline{x}_D)^2}{\sum_j (x_j - \overline{x})^2}\,,\]with \(x_j\) being the \(k\)-th coordinate of subject \(j\) in the principal component decomposition, and $D$ the set of subjects belonging to a demographic group. The clustering index lies between 0 and 1. A value of 1 indicates that there is no variance among individuals in each demographic group.

Fig. 5 in the paper. Clustering index for each algorithm and principal component.

Each face recognition algorithm has at least some principal components that are aligned with demographic groups. The authors conclude that “developing demographically-blind CFRAs that explicitly ignore face features associated with race and gender will help maintain fairness as use of this technology grows.”

Partial FC: Training 10 Million Identities on a Single Machine

by Xiang An, Xuhan Zhu, Yang Xiao, Lan Wu, Ming Zhang, Yuan Gao, Bin Qin, Debing Zhang and Ying Fu.

In this paper the authors show how to overcome GPU memory bottlenecks when training face recognition models using softmax-based loss functions on datasets with very large number of identities. They make three contributions: an efficient distributed training strategy for multi-GPU training; a softmax approximation that uses fewer identities while maintaining accuracy; and a new dataset, Glint360K.

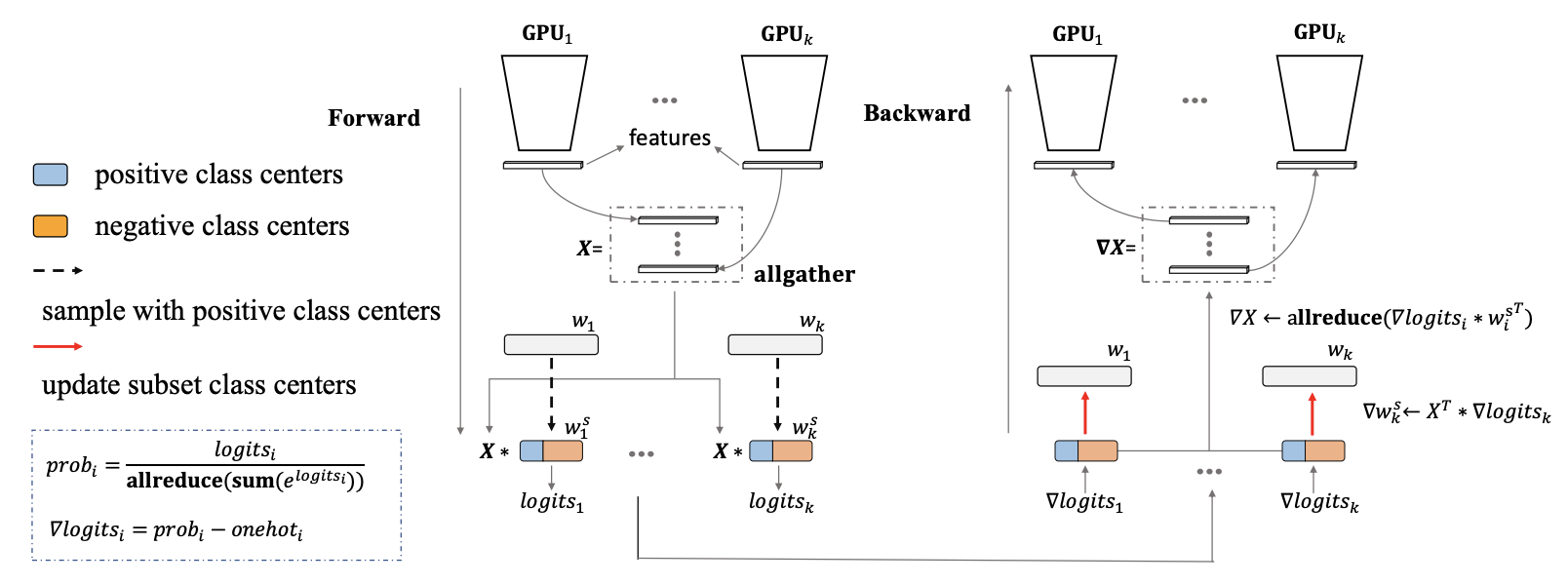

The distributed training strategy combines data parallelism for the convolutional layers with model parallelism for the softmax layer. The \(i\)-th component of the softmax layer is calculated as

\[\sigma\left(x_i\right) = \frac{e^{W_{y_i}^T x_i}}{\sum_{j=1}^C e^{W_j^T x_i}}\,,\]where \(W \in \mathbb R^{d \times C}\) is the weight matrix, \(X \in \mathbb R^{N \times d}\) is the input feature, \(d\) is the feature dimension, \(C\) the number of identities and \(N\) the mini-batch size on each GPU. The idea is to distribute the weight matrix across GPUs, let each GPU compute it’s part of the sum \(\sum_j e^{W_j^T x_i}\) and then communicate the partial sums across GPUs to compute the full sum. This is shown in the diagram below.

Fig. 4 from the paper.

After distributing the softmax layer across GPUs the authors observe that, when scaling the number of identities to millions, the next memory bottleneck will arise from the need to store all logits. So they propose to approximate the softmax function \(\frac{e^{f_i}}{\sum_{j=1}^C e^{f_j}}\) by the sum

\[\frac{e^{f_i}}{\sum_{j \in S} e^{f_j}} \,,\]where \(S\) is a subset of all identities. The subset \(S\) is selected by always including the positive identities \(y_i\) from the minibatch and then augmenting \(S\) with randomly chosen negative identities. They call the strategy positive plus randomly negative (PPRN). In experiments they show that \(S\) can be as small as 10% of \(C\).

As a third contribution, the authors combine the datasets CASIA, MS1MV2, a cleaned version of Celeb-500k as well as some additional celebrity pictures into a new dataset, called Glint360k. The dataset contains 18M images of 360K identities and as such is the largest and (according to the authors) cleanest academic face dataset.

Common CNN-based Face Embedding Spaces are (Almost) Equivalent

by David McNeely-White, Benjamin Sattelberg, Nathaniel Blanchard and Ross Beveridge.

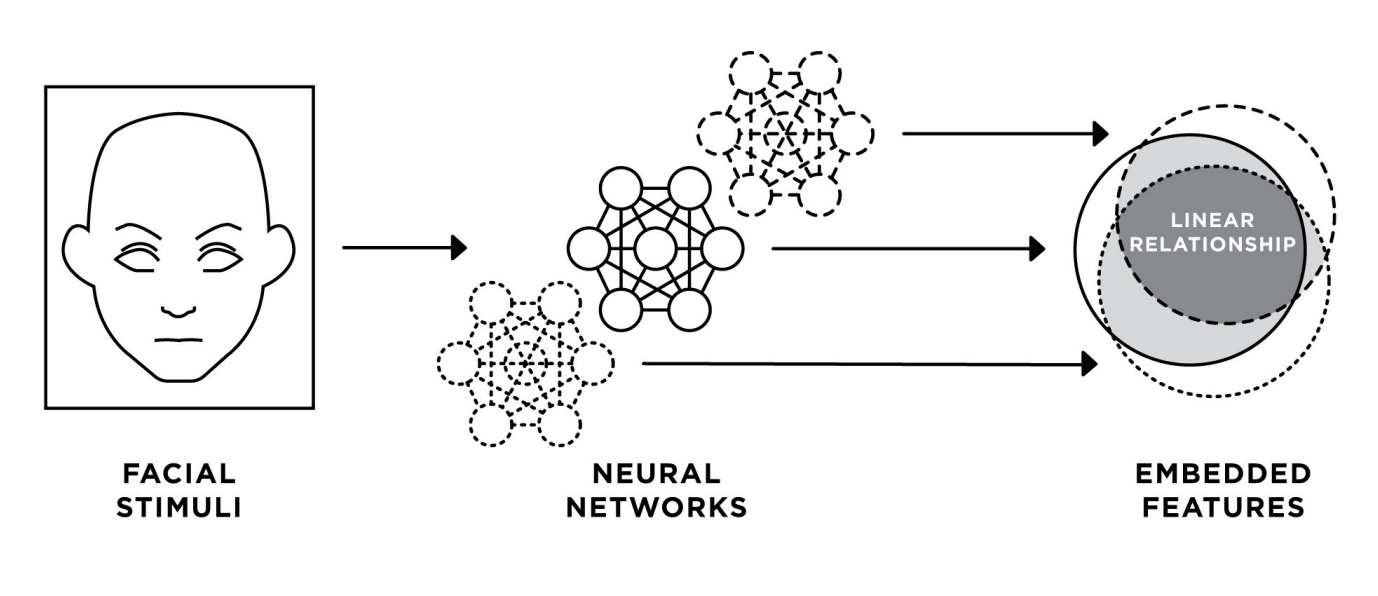

In this paper the authors ask the following question: how similar are the embedding spaces of different face recognition CNNs; in particular, if we fit linear maps between them, how much accuracy in terms of face recognition performance do we lose?

Fig. 1 from the paper.

One way to formulate the problem is as follows: given two CNNs, \(f_1\), \(f_2\) and \(m\) images \(x_1,\dots,x_m\), fit a linear map \(M \in \mathbb R^{d \times d}\) by solving

\[\min_M \sum_{j=1}^m \| Mf_1(x_j) - f_2(x_j) \|^2 + \lambda \| M\|^2_2\,.\]The regularisation is necessary, because we are solving for \(M\), which is \(d^2\)-dimensional and either \(m \leq d^2\), in which case the problem is ill-posed or \(m \geq d^2\), in which case solving it would take a long time.

The authors make some choices I don’t fully understand. First, they set the regularisation parameter \(\lambda = 1\) and don’t look at the sensitivity of results with respect to \(\lambda\). Second, they don’t fit \(M\) to map \(f_1(x)\) to \(f_2(x)\). Instead, they take image pairs \((x, y)\) showing the same person and fit \(M\) to map \(f_1(x)\) to \(f_2(y)\), in other words they map an embedding for image \(x\) to an embedding for image \(y\). But since it seems that the effect of both choices is to make the authors’ lives more difficult, we shall continue.

They evaluate four CNNs on the LFW and YTF datasets. I will leave one of the networks out of the analysis, because it is significantly less accurate than the other three. What results do they obtain: on LFW the remaining CNNs obtain accuracies between 99.03% and 99.47%. After fitting linear maps between any two pairs of CNNs, the maximum drop-off in accuracy is 0.73%. Similarly, for YTF the baseline accuracies are 91.20% to 95.51% and the maximum drop-off after fitting a linear map is 5.67%.

From this the authors conclude that “embeddings from different systems can be readily compared once the linear mapping is determined.” This is overstating their case, mostly because the evaluation sets they use are “easy” by today’s standards. A 1% drop-off for LFW does not sound like much, but achieving 99% accuracy on LFW is not difficult. The 5% drop-off on YTF is much more telling in this regard. What would be even more interesting to see, would be how TAR@FAR=1e-4 and similar metrics behave, for example on the IJB-C dataset, but unfortunately the authors do not provide this.

However, the findings of the paper are enough to conclude that embeddings from a face recognition CNN are sensitive personal data. All we need to map the embedding space of model A to the embedding space of model B are around 500 embedding pairs. That is enough to map all other embeddings from model A’s space to model B’s space. We will loose some accuracy when doing this, but we will still be able to make (noisy) inferences about the identity behind the embeddings without needing any more access to model A. This is an important point to keep in mind when developing applications.

3D-Aided Data Augmentation for Robust Face Understanding

by Yifan Xing, Yuanjun Xiong and Wei Xia.

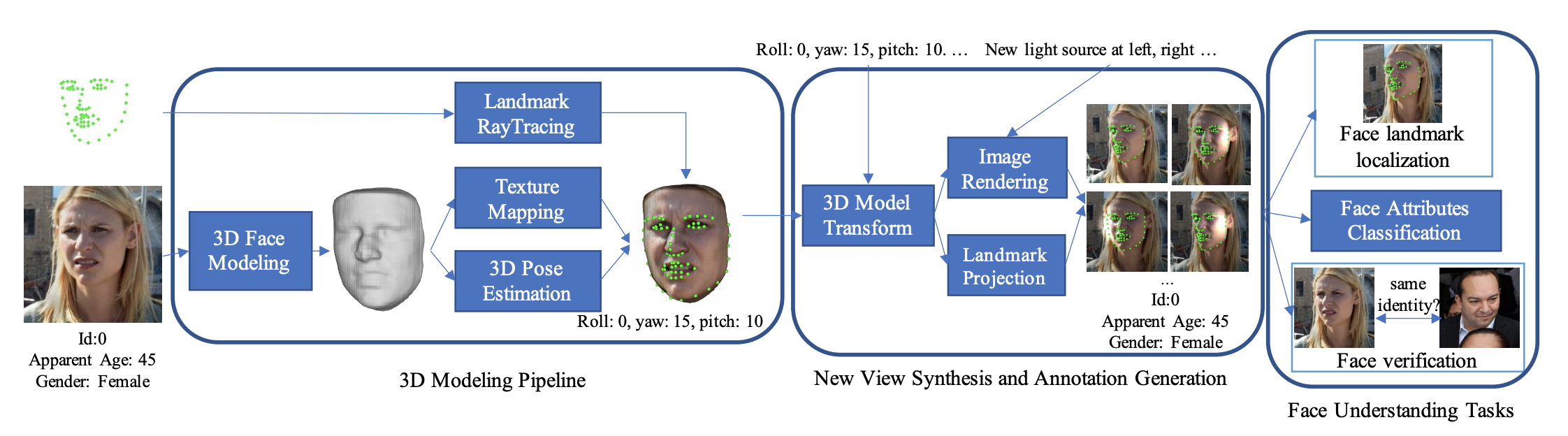

In this paper the authors propose a face data augmentation method based on 3d face modelling and evaluate it on three tasks: landmark localisation, face attribute classification and face verification.

Fig. 3 from the paper.

The authors use volumetric shape regression to infer a 3d model of the face, followed by pose estimation and texture mapping. When augmenting the pose of the model they restrict themselves to pose changes that do not expose occluded regions of the face. Finally, when rendering a 2d image from the 3d model they apply additional light sources. Note however that illumination augmentation does not improve performance for face verification.

When sampling data for training they sample augmented images with a probability less than 1/2. Furthermore, they consider the yaw angle distribution for each identity separately and only sample pose augmented images for an identity, if the entropy of the yaw distribution is below a certain threshold. The idea being that if the entropy is large enough, then the dataset already contains enough pose variation for that identity.

They train a ResNet-101 backbone on IMDB faces and TrillionPairs datasets using a large margin cosine loss and report state-of-the-art results on IJB-A and IJB-C benchmarks.

Reconstructing A Large Scale 3D Face Dataset for Deep 3D Face Identification

by Cuican Yu, Zihui Zhang and Huibin Li.

In this paper the authors attempt to overcome the lack of large 3d face datasets by reconstructing 3d faces from 2d models. They use ExpNet for 2d-to-3d reconstruction and VGGFace2 as the source dataset. When training the model, they first train on 2d images and then fine-tune the model using the normal component images (NCI) of the 3d faces.

Fig. 3 from the paper.

They achieve performance comparable, but not exceeding, the state-of-the-art on several 3d face verification benchmarks such as BU-3DFE, FRGC v2.0 and Bosphorus. As the authors themselves conclude, this work “is only a preliminary exploration of 2D aided deep 3D face recognition.”

FaceLeaks: Inference Attacks against Transfer Learning Models via Black-box Queries

by Seng Pei Liew and Tsubasa Takahashi.

In the paper the authors ask the following question: If a face recognition model is trained on dataset A and then fine-tuned on dataset B, is it still possible to make inferences about the contents of dataset A if we only have black-box access to the fine-tuned model? In other words, does the fine-tuned model leak information about the original dataset A? It has been shown previously, that without fine-tuning, an ML model can leak information about its training dataset, but does this still hold after fine-tuning.

Unfortunately, the authors don’t answer this question. Instead, their result can be summarised as follows: given access to the embeddings of a face recognition model it is possible to predict with better than chance accuracy whether a given person’s image was used to train the model. Not much better than chance though. This is a significantly weaker statement, because (a) it is known that face embeddings contain a lot of (private) information and (b) black-box access to a face recognition model usually means knowing only the similarity score between two faces.

Furthermore, the model used for their experiments achieves an accuracy of only 96.4% on LFW, while state-of-the-art is >99.5%.