What’s Hidden in a Randomly Weighted Neural Network?

Usually training a neural network means finding values for weights such that the network performs well on a given task, while keeping the network architecture fixed. The paper What’s Hidden in a Randomly Weighted Neural Network? investigates what happens if we swap the roles: we fix the values of weights and look for subnetworks in a given network that perform well on a given task; in other words, we optimise the network architecture while keeping weights fixed.

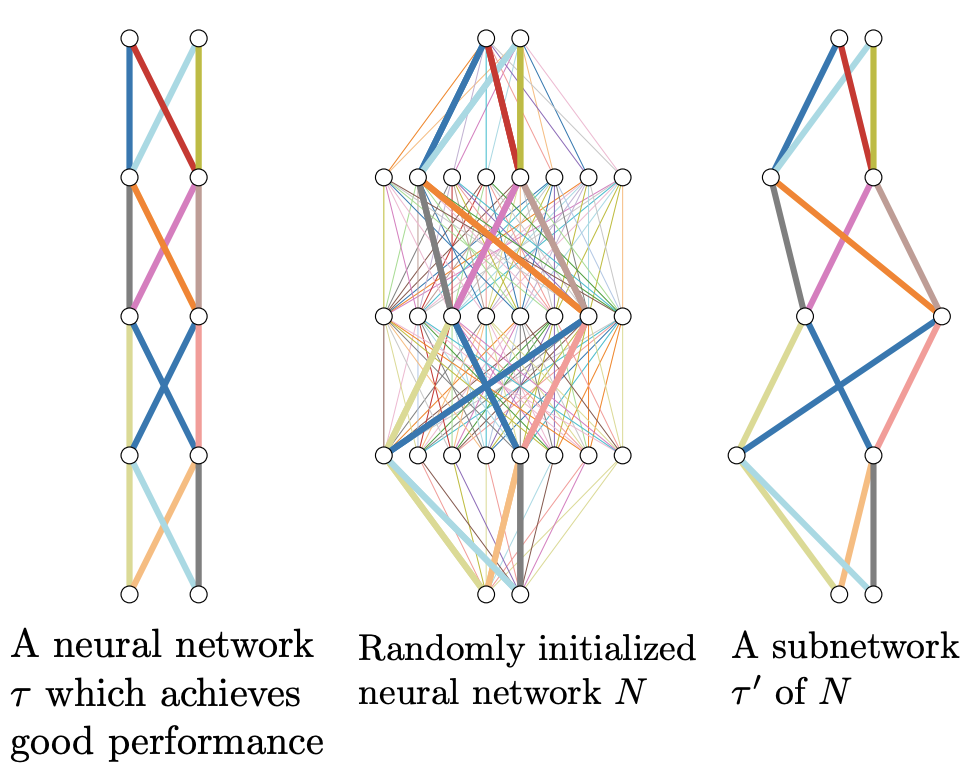

The following figure illustrates the idea.

(Source: Fig. 1 in the Ramanujan et al. 2021)

The paper provides a practical algorithm to find subnetworks that perform well on a given task. The algorithm reformulates the problem of finding subnetworks as a smooth optimization problem, which can be solved using the standard machinery of deep learning.

Does it work?

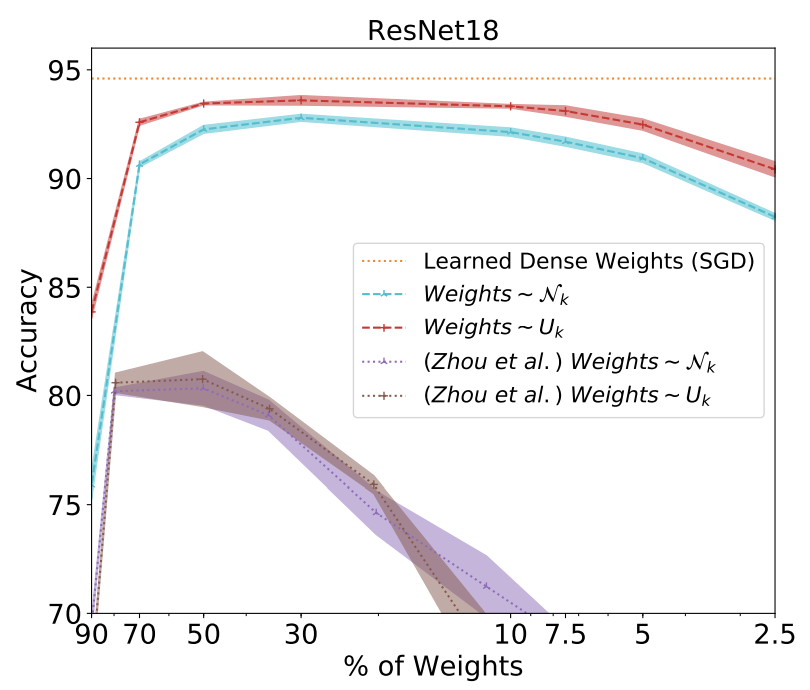

Interestingly enough, it does. The following figure illustrates the accuracy of optimally chosen subnetworks, starting from ResNet-18 on CIFAR-10, depending on the fraction of weights kept.

(Source: Fig. 11 in the Ramanujan et al. 2021)

While selecting only 30% of weights we can attain >90% accuracy, while the full network trained in the usual manner achieves ~94% accuracy. We are not far off, even though we haven’t changed the value of the weights, only removed some of them.

Are these results surprising?

Yes and no.

- No, because deep learning has taught us the fundamental lesson that given enough degrees of freedom we can interpolate almost anything. And there are a lot of degrees of freedom when it comes to choosing subnetworks. Starting with AlexNet so much effort has gone into training models for ImageNet classification, that another model achieving 74% accuracy on ImageNet is rarely news.

- Yes, because we wouldn’t expect such a behaviour from a logistic regression model or even a shallow neural network. We are used to think of the weights as storing the information in the neural network. But here each weight stores very little information, it’s value is either 0, -1 or +1. That’s it. But apparently that is enough for ImageNet.

What do these results teach us?

They are another indication that architecture contains inductive bias. We like to think of model architectures as blank canvasses with weights as the paint that forms the painting. And to some extent that is true. We certainly treat architectures as blank canvasses, because use the same standard architectures, be it ResNet or EfficientNet for all tasks. We don’t do it, because deep learning frameworks can efficiently train only a constraint set of architectures. And we don’t do it, because we don’t know how to do it. This paper shows that without touching weights, architecture alone has a significant impact on task performance. Whether or not there is a way to exploit this impact is a different question.